2025.12.27

The Genii Locorum of Saihoji

(First Part)

Matsuda Noriko & Mitachi Takashi

Standing in the Space Between Nature and Culture

The ancient Romans believed that all locations were inhabited by genii locorum —the protective spirits of places. The multilayered nature of time is a key concept for understanding the history of Saihoji. And looking over the long history of Saihoji we can feel that it is exactly such kind of place.

Saihoji has long held a special significance. Even before the temple was founded, it served as the location where the Hata clan built their kofun burial mounds and Prince Shotoku built his villa. What stories lie buried in this land where people and nature have interacted for centuries? In an attempt to unpack the “multi-layered of time,” advisor to Saihoji Mitachi Takashi had a discussion with Associate Professor Matsuda Noriko of Kyoto Prefectural University’s Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences. (Click here for an overview of Saihoji’s history.)

Matsuda Noriko

Associate Professor at Kyoto Prefectural University’s Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences. Specializes in architectural and urban history and studies the relationships between people and the land through villages, towns, cities, and architecture. Her research focuses on the themes of “cities and the land” and “the human history of shorelines.” As author, her publications include Ehagaki-no-Beppu (Beppu Hot Spring Town, the history and Image of the city: Restored from Picture Postcards in the First Half of the 20th Century), Sayusha, 2012, and as co-author, her publications include Geijutsu to Riberaru Ahtsu (The Arts and Liberal Arts), Suiseisha, 2025; Along the water: Urban natural crises between Italy and Japan), Sayusha, 2017; and Henyō Suru Toshi no Yukue (The Changing Fate of the City), Bunyu-sha, 2020.

Mitachi Takashi

Saihoji senior adviser. Distinguished Professor, Kyoto University Graduate School of Management. Holds a BA from Kyoto University and an MBA from Harvard Business School. After working for Japan Airlines, Mr. Mitachi joined The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) in 1993, where he served as co-chair of the Japan office and member of the BCG Worldwide Executive Committee. He currently teaches at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Management and sits on corporate boards as an outside director. He is also a board member of the Ohara Museum of Art.

Saihoji as seen from the water’s edge

Mitachi: Thank you for your time today, Professor Matsuda. Standing in the garden at Saihoji, you get the intuitive sense that this space is created by the layering of many different elements. Then when you walk through the garden, you begin to feel as though your senses are opening up, as if you are becoming part of the garden itself. Today, I would like to dig deeper into this feeling.

Professor Matsuda, you specialize in architectural and urban history. What are you now working on in your research?

Matsuda: My research focuses on the relationship between people and the land, and the theme of the “water’s edge,” that is to say, the boundary between land and water. In Japanese we have several words for the waterfront; one of them is namiuchi-giwa, which literally means “the edge where the waves strike.” I am interested in areas and phenomena at the intersection of two distinct domains, where the boundary is not clearly drawn like a straight line, but rather shifts back and forth like the water’s edge advancing and retreating at a shoreline when the waves strike, softly blending and intermingling with the sand. I work in these constantly shifting realms, exploring a variety of ideas as I reference actual geospatial data and other information.

Mitachi: Although I believe your official specialization is architectural history, you do your research from a perspective quite similar to cultural anthropology, don’t you? If I remember correctly, you also visited seaside villages. Your research spans across disciplines, and I believe that Saihoji’s appeal also lies in the way it combines different things.

How do you view Saihoji?

Matsuda: Most people are drawn by the image of Saihoji as the Moss Temple, and once they have actually visited, they find that they want to come again, isn’t it? That’s actually rather peculiar. When the garden was first created, the temple also had a rokaku-style structure that served as the model for both the Golden and Silver Pavilions, but it no longer exists. There are several other buildings and bridges that once existed, but we no longer even know what they looked like. Nevertheless, we feel nostalgia for the things that are no longer there—things we cannot see—and find ourselves drawn to this garden precisely because it fell into ruins and became covered in moss.

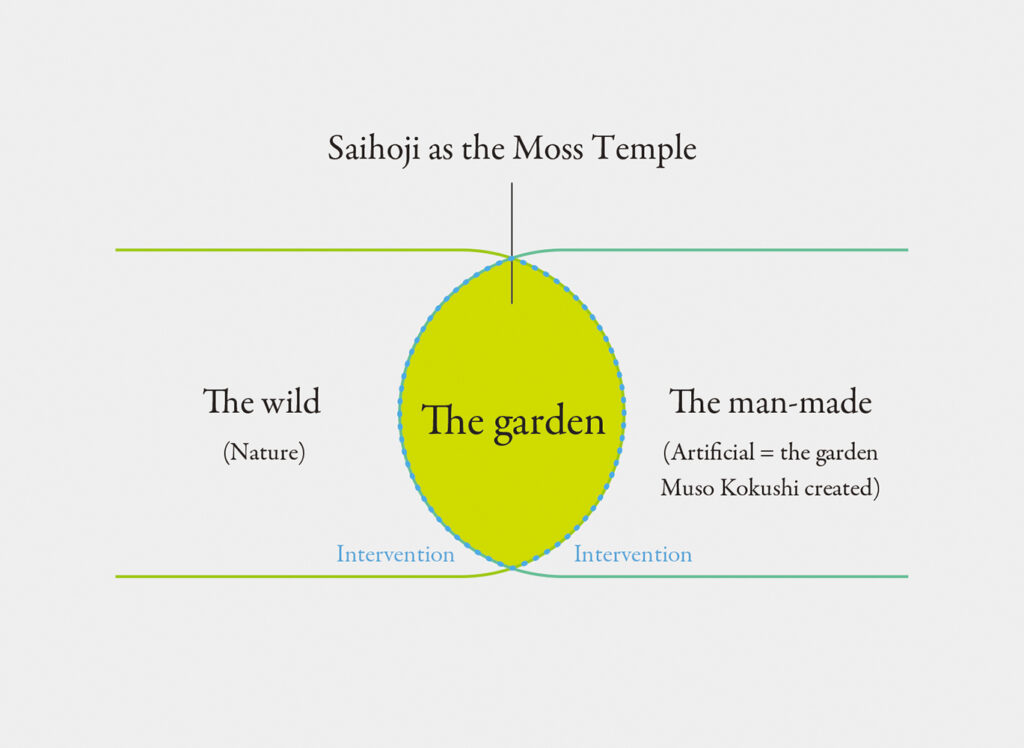

Intervening at the intersection of the wild and man-made

Matsuda: According to my interpretation, the Saihoji garden has the special quality of occupying the space in between nature (wild) and culture (man-made). Without realizing it, visitors begin to sense that there is something there.

While Western thought talks about “nature” and “culture” in contrasting terms, I would like to swap the word “nature” for “wild” to include the connotation of something more powerful.

The current garden is said to be based on an original design created by Muso Kokushi in 1339. Muso Kokushi seems to have wanted to turn the Saihoji garden into a Zen utopia, and was therefore absolutely meticulous when creating it. This garden that he created corresponds to the “man-made” part of this land. However, the same garden wound up eroded by water and moss, following repeated destruction through the flames of war and floods. That is the “wild” part. I believe that the Saihoji we now know as the Moss Temple exists in the space where the wild and the man-made overlap.

If we leave the garden as it is and stop tending to it, the wild will eat away at it, until it is no longer a garden at all.

Mitachi: But Saihoji’s garden remains a garden. What do you make of that?

Matsuda: I believe it is because the gardeners and others associated with the garden constantly intervene in the border area between the wild and man-made. I’m not talking about any major construction work, but rather the consistent, intimate, and manually performed tending to the garden that has become the hallmark of landscaping at Saihoji.

Is it not the case that these acts of constant maintenance have developed into a form of Zen spiritual practice known as samu? The fact that the garden’s maintenance is carried out by the temple’s in-house team of gardeners, and not outsourced to a landscaping company, is compelling evidence that tending to the garden is itself an integral part of the temple’s operations.

The water that fills the space between the natural and artificial

Mitachi: The words “natural” and “wild” came up, so I would like to turn our attention to the water.

Kyoto is in a basin, with a multitude of small rivers in the mountains that surround the city on three sides. People have always found it easiest to live near rivers and springs. Water is essential for life, so the best locations to live are along the banks of safe rivers that don’t overflow.

Saihoji was built in a fan-shaped plain close to the once turbulent Katsura River, where the Saihoji River now flows. Since the time when Prince Shotoku had his villa built here, the temple grounds have also been supplied with natural spring water. Judging by the sheer number of ancient kofun burial mounds in the area, we can tell that this has long been a highly habitable place for people.

Matsuda: It seems that within the entire Kyoto basin, the area around Saihoji has the highest concentration of kofun burial mounds.

Mitachi: Yes, there are kofun everywhere. According to legend, Muso Kokushi used stones from the kofun to build his karesansui (dry landscape-style) garden. No one knows for sure if it’s a true story, but if it is, using grave stones like that is quite audacious, don’t you think? Though he would probably have said that the stones are there for the living, not the dead.

In this way, Saihoji has both water and history. When you think about it that way, it’s not just moss that we have in the space between the wild and man-made. The Golden Pond also plays an important part. After all, moss cannot survive without moisture.

Matsuda: That’s right. Water accounts for a significant share of the wild.

As evidenced by the spring water that has welled up here for centuries, this land has always had a moisture-rich environment at its foundation. Furthermore, the use of water channels to divert water and create the pond demonstrates the application of civil engineering and water management techniques. It aligns with the image of Gyoki, who went around the country building Buddhist temples and initiating public works projects that benefited the people. He was also supposedly involved with Saihoji. The garden thus gradually developed into a highly sophisticated cultural, man-made space.

However, it would be devastated by floods—that is, by the inundation of water as the wild element. Yet through that same water, another manifestation of the wild grew and became entangled in the place. Moss.

Mitachi: I see. One could say that the garden pond is simply a small body of water, but as spring water, it is simultaneously also an expression of nature. It is also an achievement of civil engineering that manages to retain a reminder of the awesome power of the wild.

If I may add one more thing about the pond, when Muso Kokushi created the garden, there was no moss; it was a garden of white sand and green pines. The boundary between the Pure Land and the human world was also said to be demarcated by white sand at the water’s edge.

Matsuda: The garden pond represents the ocean. Garden representations of shores are called suhama, and gardens supposedly originated from the act of creating these suhama.

So, the artificial island we have in the garden pond was created as a representation of an island in the sea. From a Buddhist perspective, Mount Sumeru comes to mind.

Mitachi: You are referring, of course, to the holy mountain said to be standing tall at the center of the Buddhist world. It is believed that nine mountains and eight seas surround Mount Sumeru.

Matsuda: The old garden at Saihoji supposedly looked like a snapshot of these mountains and seas. It offered a glimpse of the ideal world in Buddhism.

Mitachi: This ideal world is something that human beings thought up in their heads, so it’s clearly something man-made, isn’t it. Yet, the wild element of water was necessary to give physical form to the utopia. With that in mind, you were saying that the Saihoji garden exists in the space where the wild and the man-made overlap, but it seems like not only the moss, but also the pond water is an important element of this.

This garden is the result of the interplay and coexistence of moss, water, and human action, but how is it able to maintain this perfect harmony? I would like to go one step further to ponder this question.

The second part will be released in early January.

Edited by: MIYAUCHI Toshiki

Written by: HOSOTANI Kana

Photographed by: Editorial Department

*These photos were with permission.

Up next

Most read

Your Heart

"What is happiness?"